Extracts from C.J. Bailey's Book "The Bride Valley"

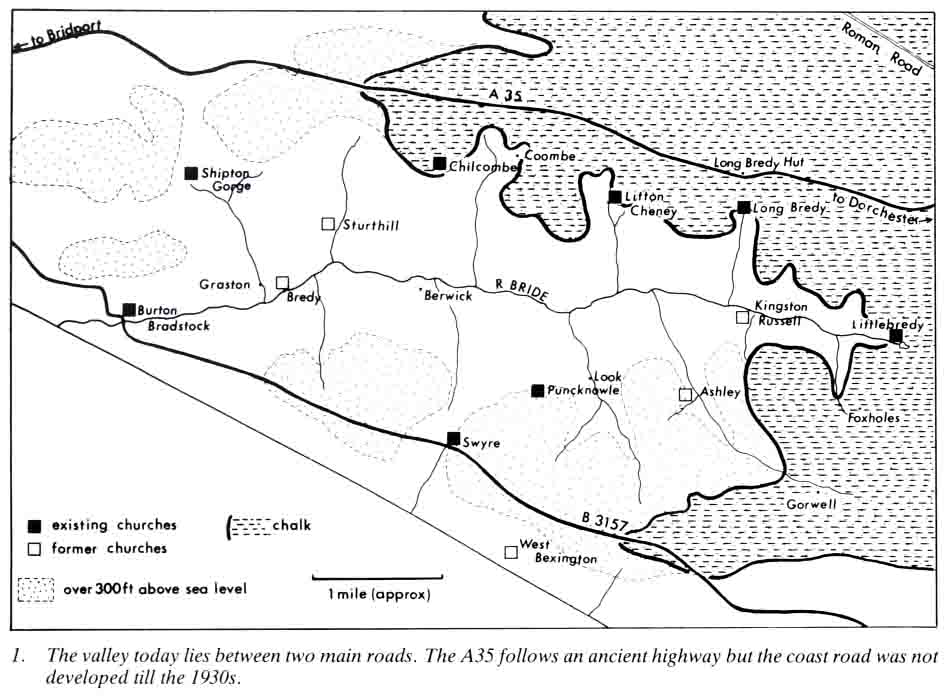

(with grateful thanks to the author and to the Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society for allowing us to re-print the pages on our web site. ) The complete book, published in 1982 and re-printed in 1995 describes the archaeology and history of the parishes in the valley of the River Bride in South West Dorset; Littlebredy, Long Bredy, Litton Cheney, Chilcombe, Punknowle, Swyre, Shipton Gorge and Burton Bradstock; and of the deserted mediaeval settlements of Kingston Russell, Sturthill, Bexington and Ashley. The book is still available from the DNHAS. We have taken just a small extract from this very interesting and enlightening book that concerns Burton Bradstock.

The Natural Setting.

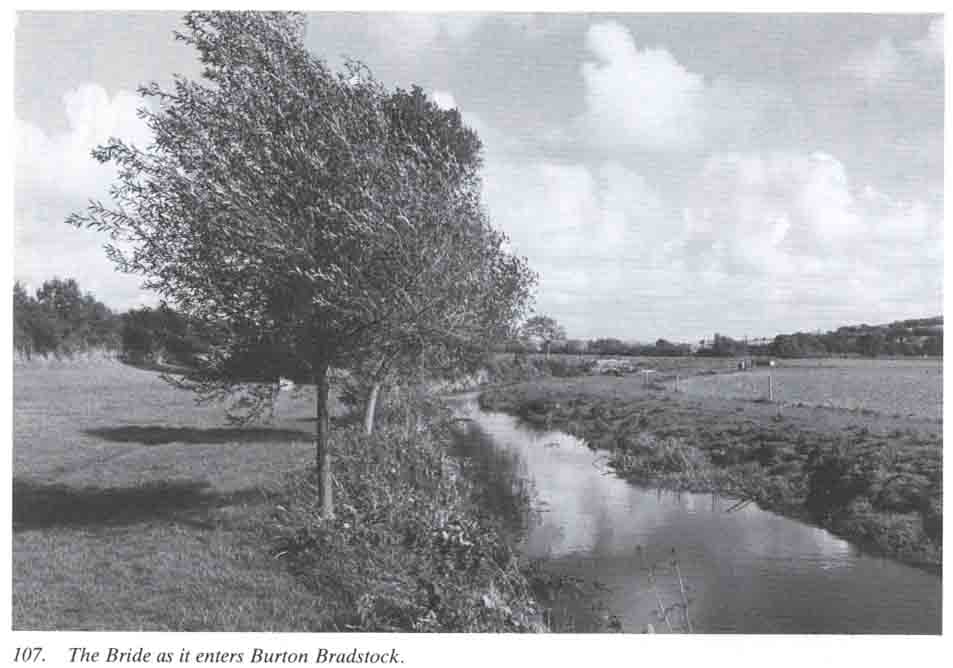

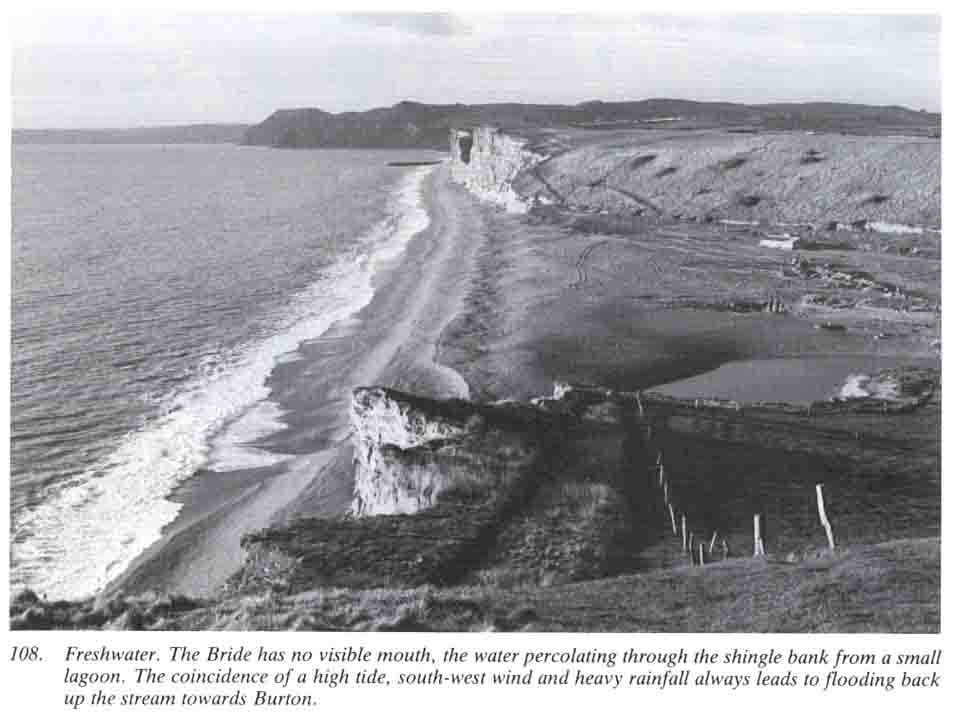

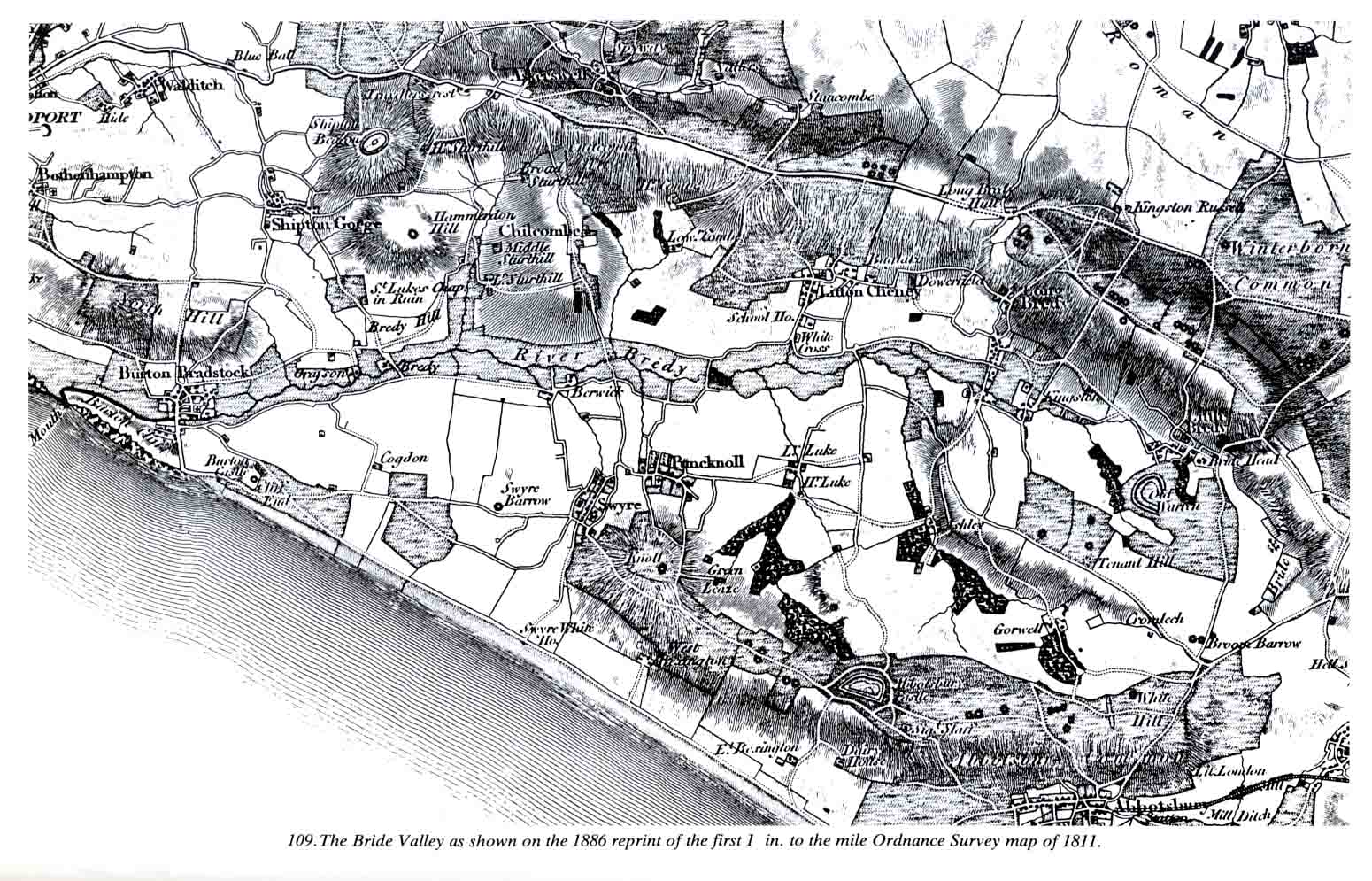

The dictionary definition of a river as a 'copious stream flowing to the sea' seems hardly appropriate for the little Bride, yet, with nine tributaries along its six and a half mile course from source to mouth, it presents a complete river system in miniature. Moreover, just as Dorset as a whole has landscapes representative of three great geological epochs, so does the 15 square mile catchment area of the Bride.

East of the source at Littlebredy a cap of geologically recent gravel lies over the chalk and forms a small area round Blagdon Hill resembling that of the heathland of East Dorset. It is, in fact, an isolated remnant cut off from the same gravel sheet which once extended much further to the west.

The chalk hills that form the head of the valley reach westwards along half its length and rise to the great undulating downland that forms the heart of the country. The chalk, and the greensand beneath it, has a steep slope from the base of which the springs which feed the river rise where water-bearing sand lies against the valley clay.

Just as the chalk, which also extended far to the west, has mostly been removed by erosion from that part of the country, so the floor of the valley has been cut down to the earlier limestones and clays. The limestone hills which flank the western end of the valley are lower and have gentle slopes.

The Bride

Any romance in the name must be at once ruled out. River names are generally far older than place names so that our forbears - Celtic, Romano-British, Anglo- Saxon and Norman and their descendants no doubt used a word sounding something like 'Bridda'. Place name experts suggest that it originally meant, in the Celtic, gushing or boiling, aptly describing the little stream which falls more than 200 feet in its first three miles.

The earliest documented reference to the Bride, is in 1288 when it is referred to as the 'aqua de Brydie' though for the villages of Longbredy and Littlebredy we have 'Bridian' recorded as early as 987. The Domesday Book spelling of Langebride for Longbredy (1086) causes some confusion. It would have been in fact pronounced 'Langabridda'. By the 15th Century we have 'Bredy' though it would still have been pronounced to rhyme with 'ready'. That form of the names is used on the 1811 Ordnance Survey Map. It is significant that the old pronunciation is still used by older people with deep roots in the valley who will say 'Longbriddy' rather than the modern 'Longbredy'.

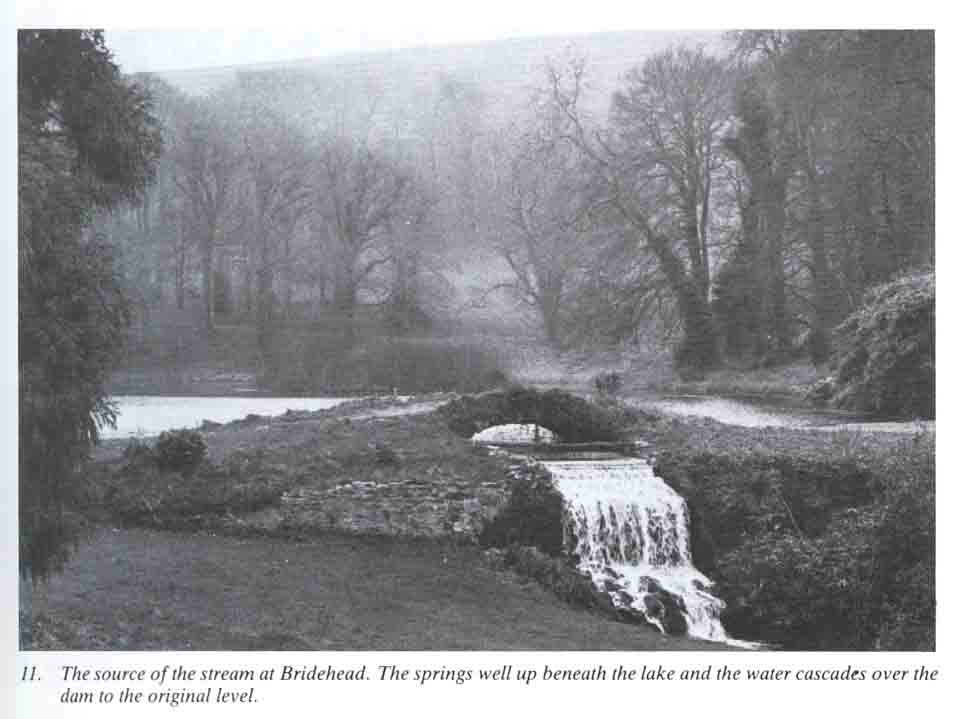

The long 'I' of Bride and the long 'e' of Bredy are relatively modern developments of the word. Indeed Bridehead as a name is no older than 1797 when Robert Williams bought the manor of Littlebredy and as well as rebuilding the house, dammed the nearby source of the stream to form a lake, and surrounded the whole with a landscaped park. The name chosen for the new estate was Bridehead.

The Valley in Prehistoric and Roman Times.

The Neolithic and Bronze ages.

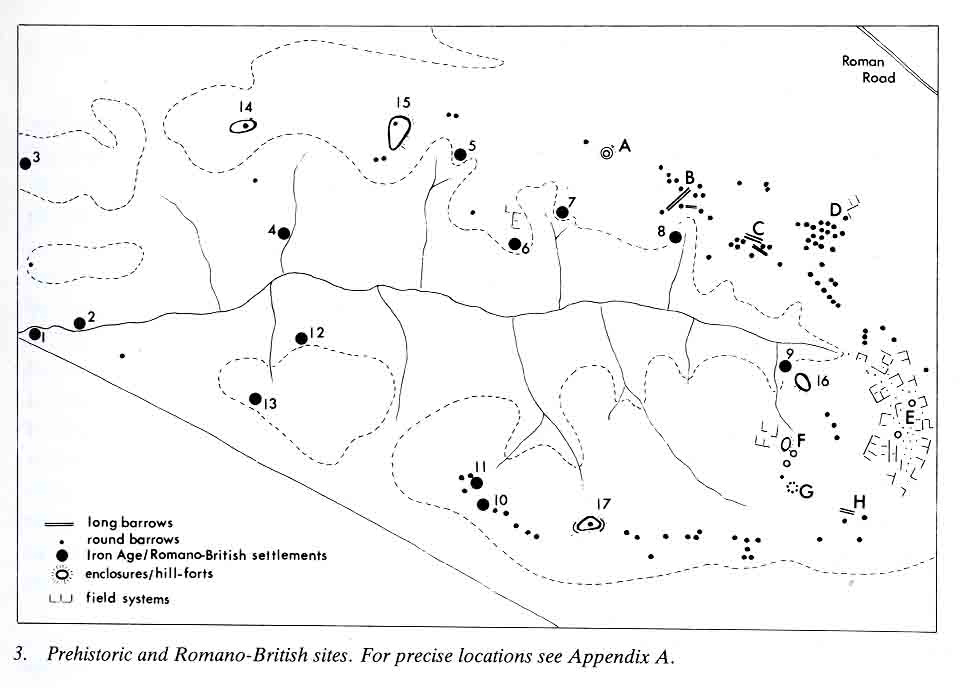

Where there is no written record our knowledge of man in the past depends largely on the interpretation of the evidence from archaeological excavation. However some of the more substantial results of his activity in prehistory can still be seen. Earthworks such as the long communal burial mounds of the ruling classes of the New Stone Age (about 3500 to 2500 BC), the individual round barrows of the Bronze Age (which lasted for the next 1000 years or so) and the earth and stone circles and field banks have in many cases by their very nature survived; they are a prominent features of the hills around the east end of the valley. The importance of the area in the second and third millennia BC is shown by the fact that the density of barrows north and east of Longbredy and Littlebredy is as high as that round the great prehistoric centre of Stonehenge. In our area, as on Salisbury Plain, they are associated with ritual earthworks and stone circles. Unfortunately we have yet to find their occupation sites. Important monuments still to be seen in the valley area marked A to G on the map and are illustrated and described in the text under individual parish headings.

Iron Age and Roman Britain

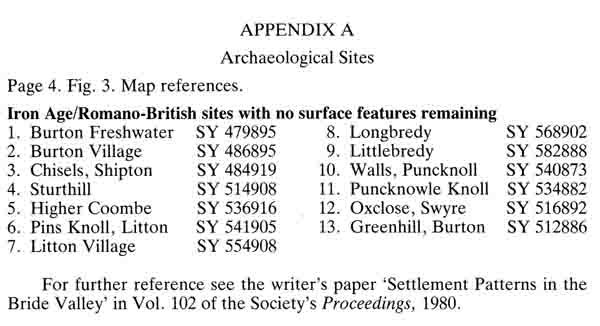

The last half of the first millennium BC saw the establishment of the Celtic Iron Age in Britain. By the time of the Roman Invasion of AD 43 Dorset formed the greater part of the territory of the Durotriges, a tribe whose hill forts are still a feature of the county. Their occupation sites, which rarely have visible remains above ground, are found by intensive field study and/or aerial photography followed in some cases by excavation. Excluding the four fortified enclosures (14-17) the sites numbered on the map were, with a few exceptions, found and followed up (in some cases with excavation) by the writer over many years field work in and around the Bride Valley.

Nearly all were Durotrigian, running on until well into the 4th century AD. The Roman occupation seems to have made little impact on the pattern of rural life in the valley. Burton Freshwater (1), Burton Village (2), Sturthill (4), Higher Coombe (5), Longbredy Village (8), Stonyhills Littlebredy (9), Ox Close Swyre (12) and Greenhill Burton (13) all produced occupation debris typical of the period. The Iron Age/Romano-British farmstead on Pins Knoll, Litton (6) was found and excavated in 1965-69. Evidence from the site of the reservoir at Litton raises the possibility of a possible Roman Villa in the vicinity and Shipton Hill (14) has produced material from very early in the Iron Age.

The excavated sites are illustrated and discussed here under the relative parishes. More detail can be found in the Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society wherein all the above sites are recorded.

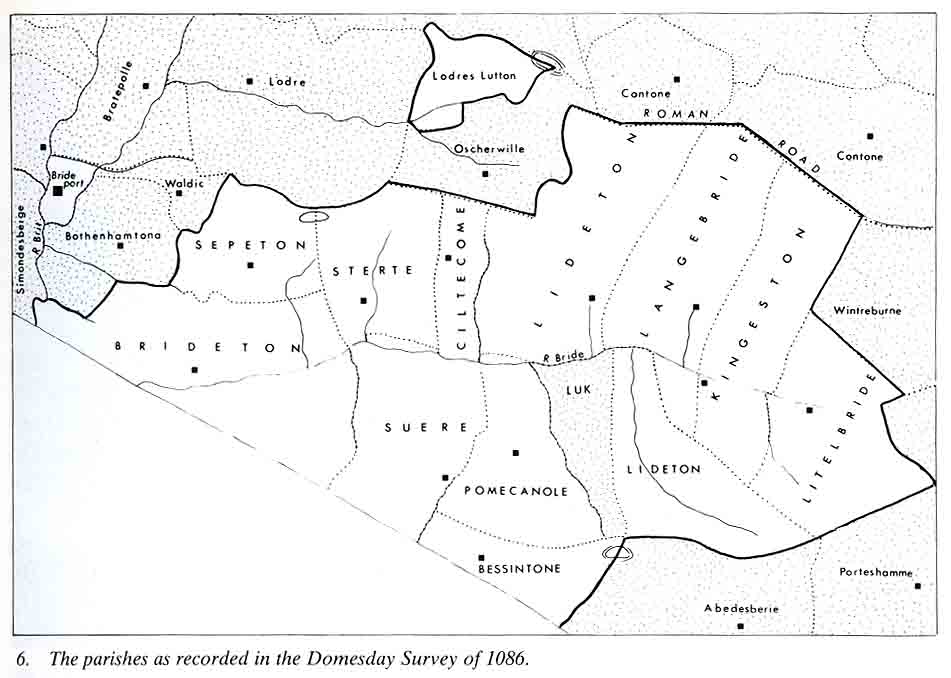

The Ancient Parishes

The parish boundaries as established over 1000 years ago were probably little changed over the first 500 years. The period from 1450 - 1550, however, saw the decay, over much of the country, of many once-thriving villages and the Bride Valley was no exception.

Bexington had been a village, certainly from well before the 11th century. By 1451 it had suffered so much from poverty and from the raids of French pirates that the Bishop ordered its church of St. Giles to be abandoned. It was further decreed that the parish should be united with Puncknowle, which was thus extended to reach the sea.

Of the mediaeval village of Sterte (Sturthill) there is today little trace. We know from documentary records that the chapel of St. Luke was served by parsons from 1240 to 1545 when it became so impoverished that the living was left vacant and the few remaining inhabitants had to use the Burton Church. Although united with the latter ecclesiastically, physically the parish was divided between Burton and Shipton.

Kingston Russell village, with records from 1280, lost its church at the same time. The village having become so depopulated the cure of souls of those left was transferred to the Rector of Longbredy and its chapel, dedicated to St. James, fell in ruin. The civil parish, however, still remains intact.

As the map shows, Litton (Lideton) was a large parish made up of three distinct parcels. To the north an isolated area, known in parish records as'Loderland', reach as far as Eggardon Hill; to the south in the triangle formed by Parks farm, Gorwell and Ashley formed another outlier; in the centre was the village and church. This untidy state of affairs was not tolerated by modern civil administration so that when Local Authorities were set up in 1889 changes were made. Loderland was shared out between Askerswell and Loders, Ashley, Gorwell and Parks Farm were transferred to Longbredy and the central block became Litton of today.

The ancient manor of Look (Luk), first record 1230, was in fact an outlier of Abbotsbury parish. Until 1889 Abbotsbury thus extended right down into the valley with the Bride as its northern boundary. This anomaly was tidied up by giving Look to Puncknowle and by compensating Abbotsbury with part of the old Bexington manor. This was done by moving the boundary line of Abbotsbury, which originally passed through the hill-fort and down to the sea, further west to pass through Tulks Hill.

It is not known precisely what factors determined the positioning of the parish boundaries. It was once obvious from the map that use was made of natural as well as man-made landmarks; hills, coombes, streams, hill-forts, barrows and the Roman road all serve a purpose. Moreover the patten seems to show fair distribution and land resources. This Puncknowle and Swyre, both hill top villages, have boundaries so contrived to reach and include a length of river in the valley below. Each could thus have a water-mill which was so vital a part of mediaeval village life. The Domesday Survey of 1086 recorded mills for both manors.

Burton Bradstock - Early Settlement

Three round barrows were noted in the parish by the Royal Commission but, without excavation, there is some doubt about their identification. Bind Barrow, overlooking the beach is the most familiar but the second element of the name could equally refer to the hill itself. A mile or so to the east of Bind Barrow, Greenhill is a limestone spur jutting out from the coastal ridge, northwards towards the valley. This was the site of another of the Durotrigian/Romano-British settlements in the area (Fig 3, No 13). It was first noted towards the end of the last century when burials were dug out of the workings of a quarry, together with their accompanying food vessels. Further finds, including Samian ware, have been found but the site is now ploughed out. In the village itself, near the anchor Inn, building trenches in 1963 exposed similar burials and pottery while, at Freshwater, yet more evidence has been found in soil eroded from the low cliffs (Fig.3, Nos. 1&2)

Brideport and Brideton

There are seven Burton places in Dorset and more elsewhere in the country. The word, as a rule, signifies a farm (ton) near an earthwork (burh) but our Burton is an exception, the first element of the name coming from the river Bride. Thus it is the Anglo-Saxon 'farm on the Bride'; Bradstock comes from Bradenstoke, a mediaeval priory in North Wiltshire, which once held a church and, probably, some lands in the parish.

A fascinating problem is presented by the relationship of the town of Bridport to the River Bride. Settlements along a river often take their names from it; along the Bride we have Brideton (Burton), Bredy, Longbredy, Littlebredy. Bridport seems, at first glance, to be named after the river Brit or Brid on which it stands; there are, however, no 'Brid' place names up the valley of that little river. Instead the names are all derived from the old name of the river which was Wooth (e.g. Aqua de Woth, the Wooth Water of 1287). They include Watton, Wooth Manor, Binghams Farm (which was Binghams Worth) and Camesworth. Place name experts agree that the name of the River Brit came from the town name and not, as usually happened, the other way around.

It seems certain, therefore, that the 'Brid' element in Bridport is, as shown by it's early form of 'Brideport', really that of the River Bride. We should remember, as well, that the extension of Bridport Borough down to the sea is relatively recent and that Burton Bradstock's western boundary was with Symondsbury along the Brit, at what is now West Bay. Recent work by the Rev. Basil Short, has identified the original Saxon Brideport as a small town, probably 'walled' with an earthen rampart, built across the river, its harbour one and a quarter miles up-stream from the later one at the river mouth. The most likely explanation seems to be that Old Warren, at Littlebredy, was the original hill top 'burh', its defences, perhaps, never completed before it was moved to a defended harbour-site in the Wooth Valley. Keeping its name, Brydian or Bride, it soon became Brideport to distinguish it from its older neighbour Brideton and, later, gave its name to its own river.

Burton Bradstock -The Manors

At the time of the Domesday Survey, Bridetona was divided into a large manor which was a part of a group held by the King and a smaller, including the Church, which was held by the abbey of St. Wandrille in Normandy. Early in the 12th century, the crown land was given to Henry I to the abbey of St. Stephen in Caen, also in Normandy, partly for the redemption of his soul and partly in return for the handing back of the crown and royal ornaments which his father had given to the abbey.

Burton thus became attached to the Benedictine Priory of Frampton, which was a cell of the Norman abbey. Like some other mediaeval landowners in the valley, as we have already seen, the Prior had his troubles, as in 1287 he had to take Peter, parson of the church of St. Mary at Bridport, and Thomas de Lodres to court for 'taking growing corn at Brideton'. The priory held Burton until 1437 when, the foreign monasteries having been suppressed, it was given by Henry VI to the Royal College of St. Stephen, Westminster.

Hutchins says that St. Wandrille held only the advowson of the church but records show that land was included with it. In 1286, these were exchanged for lands held in Normandy by the Wiltshire Priory of Bradenstoke which explains the second element of the name of the village. In 1292, the lands held by its Prior were valued at £4.6s.8d., which may be compared with the £12. 13s. 4d. of old crown manor lands then held by the Priory of Frampton. The last presentation to the church by Bradenstoke was in 1469, after which the patrons were the Dean and canons of St. Stephens, Westminster, so that it seems that about this time, the two parts of Burton came together.

After the Dissolution it was held briefly by the Crown and, in 1579, Christopher Hatton is recorded as holding the advowson. By the end of Elizabeth's reign, together with the manor, it had passed to Sir Thomas Freke and then, via the Pitts, to Lord rivers in the 1700s. These families were all related by marriage and eventually Burton, in the later 1800s, became part of the estate of Augustus Henry Lane-Fox-Pitt-Rivers which extended over 2762 acres in Wiltshire. In fact, it was said that he could, before it was in part sold off, have ridden from his house at Rushmore in North Dorset to the sea at Burton without leaving his own land. He died in 1900, internationally regarded as the modern archaeology and was succeeded by his son, whose death in 1928, much of the property was sold. Burton, however, survived until 30 years later, when it was put on the market and, what was described as 'one of Burton's golden ages' came to an end.

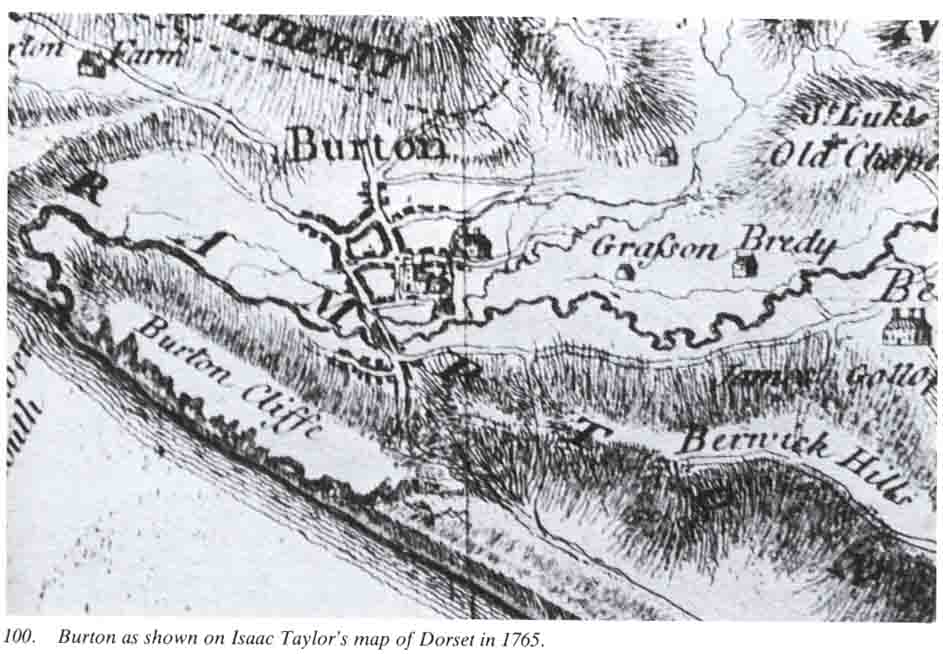

The ecclesiastical parish of Burton has always included Graston and Bredy, both distinct mediaeval manors. The end of the village of Sturthill led to a complicated division of its tithes as well as its land, some of which, as we have seen, was added to Burton. Until the late 1700s, Litton was the largest parish in the valley, both in population and in acreage but by 1839, although the sizes remained the same, Burton's population had increased almost twofold to over 1000, mainly because of the introduction of spinning mills; today, the differential is maintained and the rateable value of Burton is far and away higher than that of any of the other villages.

Burton Bradstock -The Village.

The Anglo-Saxon Brideton followed a Romano-British settlement on the higher ground just north of the river. Just how the manors of the two priories were divided is not known for certain, but an ancient boundary appears to run southwards from Bennett's Hill Farm down to Shadrach Farm and then straight on as the High Street and Cliff Road. The land between this and the mediaeval Graston may have been the original Bradenstoke manor.

Like the other villages along the coast, the main occupation of Burton was with the land, combined with the seasonal fishing from the beach. From the 17th century, Burton had the reputation of providing men both for the Royal Navy and for ships trading with the newly established colonies. This local association with the sea-going may have been further influenced by the fact that west Dorset, with Bridport as centre, had, from the 13th century, grown and manufactured hemp and flax for cordage and sails. Burton has always been associated with the cottage netting industry and, indeed, an attempt was made in the early 1500s to set up ropewalks, but this did not succeed because in 1530 an Act of Parliament prohibited anyone living within five miles of Bridport from making rope.

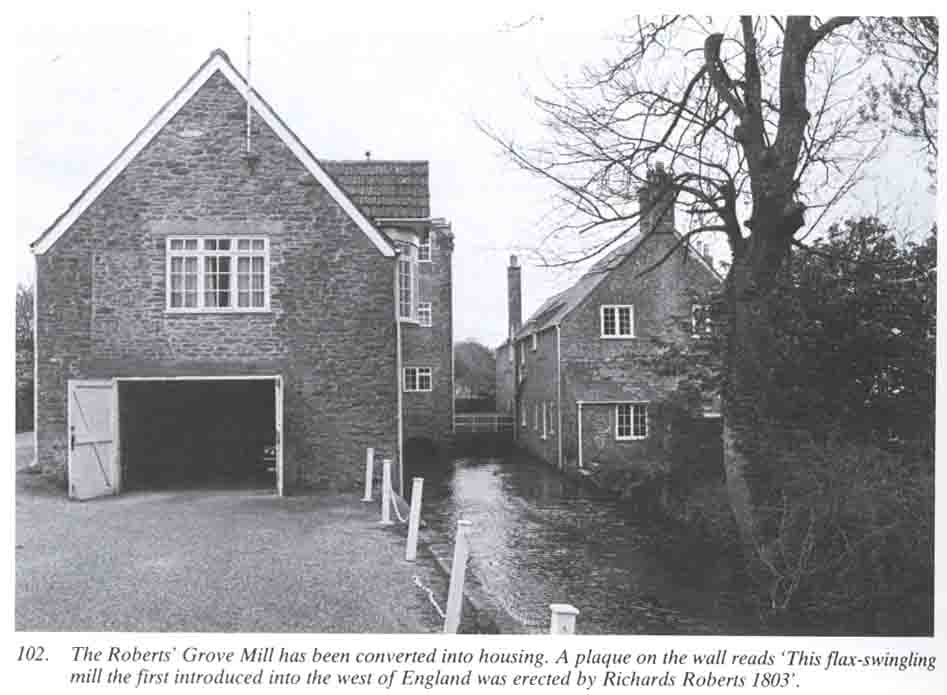

From 1794 to 1840, however, the quiet association of cottage industry farming and fishing was rudely interrupted by the Roberts family, who combined the former with the manufacture of flax. It was Richard Roberts who, having married a well-to-do Burton widow, set up water driven spinning mill in 1794, just south of the church. In 1803, further up the river, he built Grove Mill, near Grove House, which had been brought to him by his wife. This was a swingling mill replacing the age-old industry of separating the fibres by hand. His third mill, built near the first in 1813, was intended for finer spinning. Their products ranged from sailcloth to table napkins and from hammocks to tea towels. Some 50 men and women from the village were employed, but Roberts also used child labour, seeking boys and girls from workhouses, both far and near, preferring the younger girls as being generally the best workers and more obedient to command. These pauper apprentices were housed and fed in sheds which have since disappeared; they worked' not more than twelve hours a day' and were sent to the parson for two hours every Sunday to be 'taught to read and say their catechism'. All this seems very harsh, but Roberts appears to have been a just employer at a time when child labour was an accepted practice.

By 1840, the unrestricted import of raw materials, together with a lack of real interest by his sons, brought the Roberts' business to an end. By 1843, the Grove Mill was converted to grinding corn and continued to do so for another 100 years, the spinning mills carrying on with a succession of owners and varying output, the final closure coming in 1931. Meanwhile, at Burton, as elsewhere in the Bride Valley, the womenfolk supplemented the family income with their cottage netmaking as out workers for the Bridport factories.

In 1958, the sale of the Pitt-Rivers Estate marked the beginning of a change and period of growth. The village's charm, for the ever-increasing number of holidaymakers, lies in the number of 16th and 17th century thatched cottages which still remain, albeit much modernised, as its nucleus. They contrast with the modern housing estates, but like them, are now mostly occupied by older, retired people from far afield.

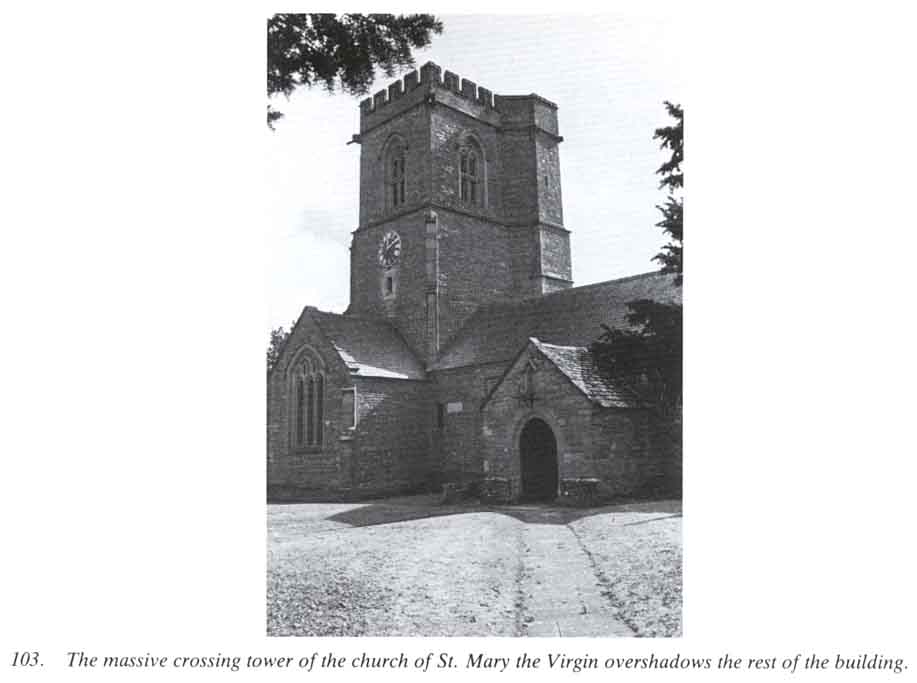

Burton Bradstock -The Church of St. Mary.

Very few churches are mentioned in the Domesday Survey but Burton was one of them and was recorded, with Bridport, as held by the Norman Abbey of St. Wandrille. It may not be mere coincidence that both have Norman cruciform plan and both dedicated to St. Mary.

At Burton the oldest part of the existing church is the north wall of the nave with two original 14th century windows. The corresponding south wall was demolished in 1897 when it was replaced, by E.S.Prior, with an arcade and south aisle added. The tower and two transepts were built in the 15th century and the chancel some 100 years after that. The roofs of the nave and transepts have barrel-vaults with carved bosses.

Hutchins' list of Rectors begins with Robert de la Wyle being presented in 1295. He also suggests that the grant of the church to St. Wandrille was in respect of the advowson only but 13th century records show that land was also involved. Thus in 1302 a jury had to decide whether 67 acres of land (i.e. ploughland), seven acres of meadow and a dwelling house belonged to the parson as a free gift pertaining to the church of Brideton or whether it was part of the lay fee of the Priory of Bradenstoke.

Shipton, as we have seen, was served from Burton and was recorded as a chapel-of-ease in the Return of the Church Commission in 1650. No mention, however, is made of a St. Laurence's chapel said to have been just to the north of the church where, according to tradition many human bones were dug up. It does seem unlikely that Burton needed two churchyards almost side by side since, in mediaeval times, burial ground was used over and over again. Hutchins, moreover, himself wrote around 1730 'the church of Burton is dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary or, as inhabitants say, to St.Laurence,' There are only two records relating to the chapel of St. Laurence, both of them in time of Elizabeth and within a few years of each other. It is just possible that they refer in fact to the parish church under an earlier dedication.

There was certainly, a mediaeval chapel-of-ease at Bredy, which must then have had a sufficient population to warrant its own little church. In the early 1300s Roger Kyngeton was 'Rector of Brideton with the chapel of bride annexed to the mother church'. Soon after there was a protracted legal argument between the Prior of Bradenstoke and Thomas de Bonevill as to who should present the parson to the church of Bryde Bonevill - from the latter name it will be seen that Thomas was Lord of the Manor of Bredy at that time. The jury found in favour of the Prior and so the attempt to make Bredy Chapel a rectory in its own right failed and it remained united to St. Mary's at Burton. There is, however, no further mention of it and it is likely that, with the decline of the population following the plague, by the end of the century it was no longer needed.

Yet another chapel is mentioned, albeit briefly, in Burton parish in the 17th century - St. Catherine's which traditionally gave its name to St. Catherine's Cross on the Shipton Road. Whether the latter marks the site of a chapel, a wayside cross, or just the name of the former crossroads is a matter for conjecture.

Burton Bradstock - Graston and Bredy

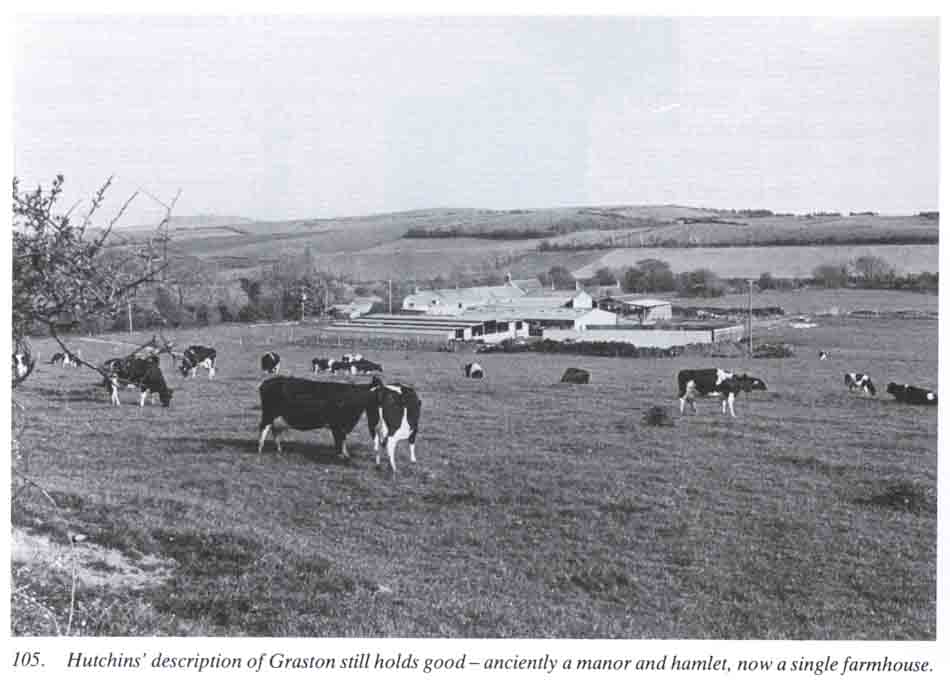

Graston Farm, on the little stream running down to the Bride from Shipton, marks the site of the hamlet of the mediaeval manor. It is the Gravstan of the Domesday Book, the second element of the name meaning stone; the first, though uncertain may indicate the grey colour of the stone, perhaps used as a boundary mark. In 1086 it was held 'of the wife of Hugh' by the same tenant as held Sturthill, paid geld for two and a half hides and had land for two ploughs. With its mill and 16acres of meadow it was valued at 60 shillings.

By the 13th century part of it at least was held by Abbotsbury Abbey; at an inquest in 1268 as to its rights and privileges of the Abbott, a gift to the monastery of one ploughland in Graveston was recorded. With additional land in nearby Shipton it continued to be held by the Abbey until the Dissolution, when, in 1545 it was granted by Henry VIII to none other than John Russell, the Berwick farmer's son who was now Lord Russell, Comptroller of the King's Household and second only in seniority to the Treasurer. From then on Graston followed the usual pattern of succession of tenants and later owners. In the 18th century it was bought by the Strodes of Parnham and 100 years later belonged, together with its neighbour Bredy, to the Hussey family.

For some reason Hutchins overlooked the Domesday Book entry for Bridie which was held by Berenger Giffard 'of the King'. Somewhat larger than Graston it was taxed for four hides and there was land for three ploughs. Around 1300 the manor was held by the Bonvil family who gave Bredy its old name Bonvil's Bredy. We have already noted the argument between them and the Prior of Bradenstoke over the chapel at Bridie. In 1320 it was recorded that, 'the sherriff has several times to cause to come here twelve of the view of Brydyebonevill, who are not related to the Prior of Bradenstoke, to recognise the right the said Prior has in the advowson of the church'. The Prior eventually proved his point and the attempt by Thomas Bonvil to make his Bredy Chapel a separate church was short-lived. In Tudor times the farm was held by the Mores of Melplash and their successors, the Paulets, most likely lived at Bredy in the 17th century. Hutchins wrote that the Paulets built the house 'as appeared by their arms on the side of it'. One hundred years later it was described as 'long since reduced to a farmhouse and much of it pulled down'

Francis and Mary Roberts's son, Francis, took over Hembury Farm over the hill in the Asker Valley and later moved back to Bredy, having married well into a Loders farming family. One of the sons of that marriage was the Richard Roberts who was responsible for Burton's short venture into spinning and weaving industry; his brother Robert, having farmed elsewhere in the Bride Valley, eventually leased Cogden Farm on the ridge between Bredy and the sea.

Traces of the mediaeval hamlet of Bredy can still be seen and the old road, with its ford over the river, is marked by a hollow-way on the east side of the Bride. The site of the mediaeval chapel is not known. Like others elsewhere it was probably used as a farm building before becoming altogether lost.

The reader will have been aware of a gap in the story of the valley. Here, as elsewhere in England, the archaeological sequence seems to end abruptly with the end of the Roman Occupation, so that how and where people were living during the so-called Dark Ages is one of archaeology's intriguing problems. It would seem, however, that the discovery of so many Iron Age and Romano-British sites close to or within the Anglo-Saxon villages must point to some form of continuity.

By the Domesday Survey of 1086 the village pattern was already firmly established and we have a picture of small communities whose life was intimately bound up with, as well as dominated by, the agricultural economy of the mediaeval manor. It is likely that the landscape as we know it was already emerging by the end of the 12th century. The lynchets and abandoned fields on slopes where cultivation seems impossible are evidence of the need to feed the expanding population of the next 150 years. This was followed by the decline brought about in the main by the Black Death which we know struck heavily in the valley. In the following years sheep farming increased at the expense of arable land and the valley must have carried many of the 6000 strong flock owned by Cerne Abbey in 1535.

The years following the dissolution of the monasteries saw the rise of new land-owning families, some of them former tenant farmers who now had the opportunity to buy land they had once rented. Such were the Hurdings of Longbredy and the Hodders of Litton. Other older-established families moved into the valley to acquire land and this continued into the 18th century with the Napiers at Puncknowle, the Michels at Longbredy and the Mellors at Littlebredy. The slightly later Williams estate which followed the Mellors is the only one to survive intact.

The last century saw village life reach its peak. Each community was inward-looking towards its own craftsmen - brewer, baker, blacksmith, shoemaker, butcher, wheelwright, carpenter, schoolmaster - all these were represented at Litton in 1859. The beginning of the present century brought little change until the impact of the First World War and the subsequent rapid development of the motor car had their effect.

The decades following the Second World War, well within living memory, have been marked by the acceleration of change common to the whole of the country and this still continues. Mechanisation of farming has taken the place of the workforce once necessary and the few younger people living in the villages find work mainly in the towns. With the modernisation of old cottages and the building of new houses, particularly where mains drainage has been provided, the drift of working people away from the villages has been compensated by an influx of retired couples seeking refuge from city life. Happily a new kind of village is emerging combining the old and the new; sadly it lacks that sense of interdependence which was once the hallmark of village life.

.